- Home

- A. K. Blakemore

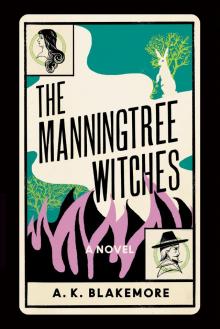

The Manningtree Witches

The Manningtree Witches Read online

For Paul Blakemore

. . . then they all consult with Satan to save themselves, and Satan stands ready prepared, with a What will you have me do for you, my near and dearest children, covenanted and compacted with me in my hellish league, and sealed with your blood, my delicate firebrand-darlings.

MATTHEW HOPKINS

The Discovery of Witches, 1647

Contents

1643

1.Mother

2.Crone

3.Maiden

4.A Discourse

5.Boy

6.Divination

7.Catechism

8.Fire

9.Maleficium

10. Sermon

11. The Incubus

12. Mass

1644

13. Vagrancy

14. Warrant, Testimony

15. Fornication

16. Arrest

17. Coven

18. Iconoclasm

19. Suspects

20. Colchester

21. Gaol

22. Chapel

23. Witchfinder

24. Lonely Men

1645

25. Cadaver

26. Confession

27. Court

28. Execution

1647

29. Foreknowledge

30. Contrition

31. The Book

32. Consumption

33. Felon

34. London

35. The Devil

Afterword

Acknowledgements

1643

If our witches’ phantasies were not corrupted, nor their wits confounded with this humour, they would not so voluntarilie and readilie confesseth that which calleth their life into question.

REGINALD SCOT

The Discovery of Witchcraft, 1584

1

Mother

A HILL WET WITH BRUME OF MORNING, ONE hawberry bush squalid with browning flowers. I have woken and put on my work dress, which is near enough my only dress, and yet she remains asleep. Jade. Pot-companion. Mother. I stand at the end of her cot and consider her face. A beam of morning light from the window slices over the left cheek. Dark hair spread about the pillow, matted and greasy and greying in places.

There is a smell to my mother, when she is sleeping. It is a complicated, I think, mannish smell. I smelled a like smell when I was sent, as a little girl, to fetch my father away from the Red Lion and to supper. The inn would be clattery with men’s voices and small-beer sour, and my father would be very jolly indeed, sweeping me up and kissing me on my forehead, his coat crisp from the rain in the big fields. Then we would walk from the alehouse back up the Lawford hill together, my tiny hand in his much larger. That was fifteen years ago, Father long dead.

So my mother—who is at present snoring fit to wake the Devil, as they say—and I sleep together, side by side, in this one chamber in the house the fifteen-year-dead man built for us. A house of three rooms, meanly furnished: two beds, one window, plaster blue with mildew. Things being born in the walls, I suspect. I know all the noises of her flesh, and all her complicated, mannish smells. I was in her flesh once, strange to think. Flesh of it, her flesh.

I force myself to look at her face for a very long time, and to consider it closely. It is so still that at first it might seem like a death-mask, or a statue’s face. But even motionless, it is not so serene as any monument I have ever had the pleasure to see, be it by chapel or church, in Manningtree nor Mistley (not that there are many such images left in Essex at all, now Dowsing and his rooters have done their work, peeling the blithe lead martyrs down off St Mary’s and holding a bonfire for them over on the village green). Even in repose, my mother’s character seems to shape every plane and furrow of that dry face like a maker’s stamp on a horrid little pat of butter. Her Christian name is Anne, but she is called the Beldam West. It suits her, because it sounds wide and wicked; the sound of it is like the name of some dusty place in the book that God might drop big meteors upon. Beldam. Belle is a French word, meaning beautiful (which my mother is not, though they say she was, once). And dam like damned. Over which I suppose it is not my place to speculate.

I take her apart now, while her repose affords me the opportunity, and consider her piece by piece. Her nose is long and set in a crooked shape, having been broken. It was broken at least once, to my knowledge—four years ago, by a most wonderful righthook from Goody Rawbood as the two of them quarrelled in the herb garden on a spring afternoon. I do not remember what the substance of their falling out was, on that occasion, but I do remember the hooting of the men who had gathered at the fence to watch. I remember the blow was struck. I remember how my mother tottered back into a rosemary bush with a hand clapped over her face, blood streaming sticky between her fingers, and raised a sweet fragrance as she tumbled down onto her cules amid the little blue flowers. I can barely keep myself from laughing aloud when I smell rosemary, to this very day. Goody Rawbood is dead, of course—as people who wrong my mother have a way of ending up. See how the smell and look of her leads me to other things, other places. Or else my understanding of other things and other places comes through the smell and look of her, and that is what it is to have a mother.

But no more digressions. My mother’s cheeks are hollowed out, the skin stretched over them tight and brown. The unwary blade of sunshine from the window whitens the very fine down on her chin and her temple, and refines the thin lines age has lain at the corners of her eyes and around her mouth, like a cat’s whiskers. Her forehead is pink with sunburn. The skin around her neck is loose, as though those folds are easing into their good fortune at having been spared proximity to the cruel eyes and sharp tongue that so disfavour her among our neighbours; a neck like a fat hog’s wattles, baggy and discoloured and appalling.

My mother’s mouth is the worst thing. She holds her thin lips slightly open as she sleeps, and they are raw and dry at the corners, where a sediment has gathered. Looking in through this red opening you can perceive her mouth’s interior satin, and see how her teeth are stained from chewing tobacco, how the wet root of her tongue jostles, as though she is dreaming a conversation. Or, more likely, a row.

Here is my very unchristian thought: I wish I had something horrible to hand to put into her mouth. I imagine I am lowering a wriggling mouse between her lips by its pink tail, then clamping my hand down over it. Or no. A jar of hot horses’ piss, a fistful of rabbit droppings, blood—pig’s blood—hot from the slice—

My mother’s eyes open, and she says my name, quietly: “Rebecca? Beck?”

“It is I.”

She mutters something I do not hear, and presses her hand to her temple. She groans. “Never get old, Rebecca,” she says. “Mind me, girl. I am all filled up with aches and pains before the work of the day is so much as thought of.”

I answer that her aches and pains might have more to do with the Edwards’ small-beer than anticipation of honest labour. She is a very great drinker, and often says that drink does more than God in the way of comforting the poor man (or woman, for that matter, she will add, with a wink of her black eye).

“Mind thy tongue,” she snaps back, wetting up her lips. “And utter not that name in my house,” she adds, sleep-fuddled and haughty in even measure. Utter is the very word she uses, thinking herself Moses.

I ask her if the name Hobday is still quite well to the ears of God and man. “Because I’ve some linens to take to the Hobdays up the hill.”

Mother has risen from her bed now, and gropes for the chamberpot. She squats down by the side of the bed and draws her wrinkled smock up over her knees, relieving herself. Her piss is a dark yolk-yellow colour in the mornings after she has been out drinking, and it sme

lls yeasty, causes the whole room to smell yeasty. This is the smell of Friday—and Saturday, too, most usually. When she has finished she shakes herself off with a few jerks of her haunches and clambers back into the cot. Hot little room, the spring sun coming in from the east. Layabout. “Take some milk-pottage for Bess,” she says, yawning. She lowers herself down and draws the coverlet over her breast, closing her eyes again. I wait there at the end of the cot for any further order or imprecation, but none comes.

Vinegar Tom bolts in through the door as it is opened, and leaps up onto Mother’s bed. He mews a dismissal over his shoulder at me, and settles down by the Beldam’s hip to lick the summer night off his fur. She lowers her hand to scratch at him between the ears. “Impudent girl,” my mother murmurs, “thou backwards paw, thou whelk.”

I am very grateful to close the door behind, to shut away the creature that made me.

It is early in the morning. A nice big cream of cloud settles on the horizon. Out in the yard, one of the hens takes a considered step, her head held askew, like a woman in marvellous skirts stopping to check the tread of her boot for a stone.

2

Crone

MANNINGTREE AND MISTLEY ARE TWO VILLAGES that together add up to something like a town, fitted tidy as pattens, left and right, tucked neatly by the waters of Holbrook Bay on the crook of the Stour. When the tide is in, the blue slice of water jostles with little fishing boats and the hoys of merchantmen, and their rigging makes a marvellous cutwork of the sky. By night, they say smugglers make use of the waterway to go inland, carrying braces of French pistols and pyxes and gilded prayerbooks in Latin, which is the black speech of the Pope. When the water draws out, it leaves behind wide beds of soft silver mud where sandpipers, curlews and godwits scratch slender trails in their digging about for worms. It smells good or bad, depending on your point of smell—of sea-scum, bird shit and wrack drying up in the sun. There is one long, narrow road that runs alongside the riverbank, from the little port of Manningtree and the white Market Cross to old St Mary’s Church in Mistley. Along this road is where the people live, for the most part, in some few dozen houses hunched along in various states of disrepair and flake, all mouldy thatch and tide-marked, half-tended gardens and smalls drying on lines that hang window to window across the muddy street. Smaller ways and alleys lead up away from the river from this one road, and into the rolling hills, and the fields where the true wealth of Essex chews cud in the fields: cows, warm golden and with fat udders so full with milk it makes your own tits ache just to look at them. Up in the fields is the world of the herds, as the valley and water is the place of birds. And the herds mill about the neat little manor houses of the yeomen and petty gentry to whom they belong (and those yeomen, from their vantage point at the top of the valley, can look down their noses very well at those simple folk who live by naught but the river and their wits at the bottom).

The old Widow Clarke also lives among these rolling hills and fields. Masters Richard Edwards and John Stearne—who is the second-richest man in Manningtree—must climb out of bed in the morning, throw open their damascene curtains, and have their vista of plenty, otherwise sweet and green as a good pea soup, ruined by the sight of her little hovel stuck in the middle of it all like a hard nub of gristle, with the jutting gables and baggy thatch, and a meagre garden choked with brambles and vetch.

There is a fine blue sky, and I might make enough work to keep me far away from my mother until sundown, so I am quite cheerful, and do cheerful-person things, like whistling while I walk, and swinging my basket of pottage quite carelessly in the way that my mother would smack me upside the head if she chanced to see. The heifers in the fields are warming their sides in the morning sun, and pay me little mind. Once I am done at the Widow’s I will go directly to the Hobdays’, further up, to deliver their nice linens and mended shirts. The Goodwife Hobday is a kindly woman—no doubt she will slip me a few extra coins for my trouble. Perhaps a slice of plum cake, too. Maybe we will sit by the hearth a while and talk of Manningtree’s comings and goings: what strapping lad has joined up with—or been pressed into—the militia, what the dark young man recently come from Suffolk might want with the lease to the Thorn Inn over in Mistley.

When I reach the Widow Clarke’s house, I stop at the gate. The front door stands wide open, and there, by the worn stone of the entryway, sits a rabbit, milk-white. He is looking at me askance with a red cabochon eye. Rabbits are a common sight in these fields, scramming into the long grasses from the herdsmen’s heavy trampings, but I have never seen one like this before, a rabbit white-all-over. It has no obvious business being there—so brazen and unblemished—by Bess Clarke’s dirty stoop. His nose twitches, but the creature is otherwise wholly still, with that peculiar blood-drop of eye trained directly on the gate where I stand. The whiteness of it makes it quite an eerie sight, as if there were no real shape nor weight to it, and we consider each other for the best part of a minute before I push at the gate and call a wary good morning to the Widow Clarke. A bustle comes from within, and the white rabbit at last jerks to attention and absconds into the undergrowth. Elizabeth Clarke appears at her front step, rubbing one hand on a sordid apron and grasping at the lintel with the other. “Rebecca West,” she says, screwing up her eyes against the wholesome sun, “good morrow, sweetheart.”

I have asked the Widow Clarke how old she is before, but she was not exactly certain. One need not look at her for long to conclude very. Old enough that time now seems beneath her notice, and she’ll spend a good deal of it doing whatever nonsense she pleases. She is in possession of the full complement of ailments that afflict the elder folk of Manningtree, though usually discretely: her little paw-like hands shake with a palsy, her runny eyes are clouded, and her mouth nearly toothless. She has even lost a leg, somewhere, somehow, someway. I have seen men crippled like that—those who went away to fight in France or the war in Scotland—but never a woman. I suppose that once a woman reaches a certain level of excessive superannuation her critical limbs might simply begin to give out and fall off, much as the teeth do, and as does the hair. Perhaps the Widow Clarke’s left leg is buried unmarked beneath a patch of scrub right there in that disorderly garden. Perhaps she simply stood up one evening to find the connective gristle that attached it to the rest of her worn to a thread, and threw it on the fire with the chicken bones, a hey-ho and a shrug. This is what I see, looking at the Widow Clarke—a withered and slatternly old woman. Other people must see her differently, though, because they think her cunning. Many is the maid who’s gone to Mother Clarke for tongues, charms and scratchings, to cast the shears and sieve and beg Saint Paul for the name of her husband, or know if the first babe she gets by him will be girl or boy. I think it is the Widow’s web-in-the-eye that makes people believe in her cunning. Beyond the uncanny way it makes her look—like a fairy came along and scrubbed the meats clean of spots—people get terribly superstitious about such things as cataracts, and choose to believe that God would not be so cruel as to rob an old woman of her earthly gaze without equipping her with a spectral one, to say sorry. You would think they had never read the Book of Job. There is a rumour that tells that she was struck by lightning, once, on All Saints’ Day, and lived.

“The Beldam sent thee,” says Widow Clarke, as though this were special knowledge given her by God, and not an occurrence common to every Saturday.

“There was a rabbit by your door just now,” I tell her. “It was the queerest thing.”

“Oh. Aye?” The Widow Clarke scratches her face incuriously.

“White as snow it was. And with red eyes.”

She shrugs. I follow her into the house. One room with the windows all boarded. The only light within comes from the open door and a low fire chuckling in the grate. I begin to set out the pottage and clear away as best I can the remnants of the last evening’s repast, tossing a few dry crusts out over the threshold and into the garden. The tiny house smells dank as a burrow. The Widow lowers hersel

f down onto a stool, indifferent to my busywork. She has a peg leg of old, deeply scored wood, but she is not wearing it now, and she moves around the cottage by handing herself from one outcrop of battered furniture to another.

“Many years ago,” says Mother Clarke—and I can tell it is not a “says” so much as a “begins”—“Many years ago,” she begins, “not much after my James was born, we were living up in East Bergholt. Well. It must have been about noontime, for the sun was very high, and casting long shadows all about the yard. I had put the babe down to rest and was going to take some feed for the chickens, when I saw the strangest thing. A leveret, black and brown, sat not a yard from the threshold. She played and flitted there for some minutes, as I recall. All long shanks and ears pointed and black at the ends—black as soot. In the middle of the day and in the middle of my yard.” I half-listen to the Widow Clarke as I set to sweeping the stoop as best as I can with the bundle of rushes that serves her for a broom.

“Like she was dancing there. Not a yard from my threshold,” she repeats, idly plucking at the strings of her little stained cap. “I did wonder at it.”

“I’ll bet you did,” I say, sweeping the table now.

“They say there was a great queen who lived in these parts once, and that she went to fight the pagan invaders who came from o’er in France. They say the morning of—”

As soon as the pagan invaders get to be involved I think it time to look to my own leaving. I straighten up at the stoop and give the old woman my best huff, pushing my cap back. “Really, madam,” and, setting my hands on my hips, “what nonsense is this?”

But on she goes as if she hasn’t heard me. “They say the morning of a great battle, as she was riding out into the fields in her golden greaves and mantle, there, a hare, a little leveret just the same, ran out before her horse. And that”—here she raises her head to look at me with a mysterious smile—“the queen died that very same day, slain by pagans. An omen, see,” she adds, for my better understanding. “Hares.”

The Manningtree Witches

The Manningtree Witches